Articles - Page 2:

EARLY WATER SOURCES FIRE CRIME

LAW ENFORCEMENT HOTELS SOME EARLY CLUBS

KU KLUX KLAN M.H. HAGAMAN CIVIC IMPROVEMENTS

JOHN McCLESKEY MOVIE THEATERS EARLY SCHOOLS

EARLY WATER SOURCES - The

lack of a dependable

source of water was a

major problem confronting

the new settlement of

Ranger. One of the first

attempts at solving the

problem was a well dug in

the middle of Locust Street

(later called Main Street)

about half a block west of

the present intersection

of Main & Commerce Streets.

EARLY WATER SOURCES - The

lack of a dependable

source of water was a

major problem confronting

the new settlement of

Ranger. One of the first

attempts at solving the

problem was a well dug in

the middle of Locust Street

(later called Main Street)

about half a block west of

the present intersection

of Main & Commerce Streets.

The well was not a success: the water had so much mineral content

that it wasn’t useful for domestic consumption, and even livestock

were reluctant to drink it.

Another early source of water was the “Rock Hole,” as it was called,

in Bull Hollow, which was eventually dammed to form Hagaman Lake.

Cisterns supplied some water, and still another source was the “Big

Hole” in Colony Creek near present-day Merriman. Much like the

milkman of later days, the “waterman” made the rounds distributing

water to customers.

Before there was a dependable municipal water supply, some drinking

water was shipped in from Mineral Wells and sold for 75 cents a

barrel. Vendors sold water for 5 to 10 cents a glass downtown. One

water supplier was Ranger Distilled Water Company, which sold what

it advertised as “purity” water.

Ranger Water Works Company was organized in 1898. It used as its

source what was known as the Rice tank (the owner was Ranger business-

man J. M. Rice), about a half mile west of the business district.

Another source of water was the Riddle tank (I could not verify the

location), which was used to supply cotton gins and possibly some

residences. Ranger Water Works Company was able to take care of

Ranger’s water needs fairly adequately from these sources until the

oil boom, when a huge increase in population made another solution

necessary.

M.H. Hagaman, businessman and rancher, had built a dam across Bull

Hollow before the oil boom, forming what became known as Hagaman

Lake. Texas Pacific Railway Company had laid pipes from the Lake

to Ranger and was using the water for its engines.

The Company agreed to allow the city to use Texas Pacific Railway

Company pipes to bring water into town for municipal use. M.H.

Hagaman founded the Hagaman Water Works Company. The Company’s

filtration plant at the Lake could handle 600,000 gallons a day.

Hagaman Lake remained Ranger’s source of water until Lake Leon,

dedicated in 1955, took its place. Photo courtesy of Ranger

Historical Preservation Society.

FIRE - Ranger had little

fire protection in the

early days, especially

before there was a

reliable municipal water

supply. Before the city

incorporated in 1919 and

got what was at the time

considered modern fire-

fighting equipment, fire-

fighting was done by

volunteers, often in bucket

brigades. Sometimes fire-

FIRE - Ranger had little

fire protection in the

early days, especially

before there was a

reliable municipal water

supply. Before the city

incorporated in 1919 and

got what was at the time

considered modern fire-

fighting equipment, fire-

fighting was done by

volunteers, often in bucket

brigades. Sometimes fire-

fighting consisted of several men running into a burning building

and carrying out everything they could. One early newspaper

account described how men rushed into a burning saloon and

carried out the bar.

Fires leveled entire blocks. A major fire on April 6, 1919 destroyed

buildings between Rusk and Marston Streets on the north side of Main

Street (pictured here). Another fire sometime in 1920 destroyed

several buildings on Pine Street. Fires were devastating because

of the lack of equipment and water and the fact that many of the

buildings were wooden.

Ordinances were passed requiring new construction in the commercial

area to be fireproof. Ironically there was still enough wood and

other flammable material in these “fireproof” buildings that a number

of them eventually burned. A 1920 newspaper article reported on

four fires on the same day that destroyed the El Paso Hotel, a

residence, and a stable of 32 fine draft horses and threatened

buildings in the downtown area. The McCleskey Hotel, Ranger’s

pre-eminent hotel during the oil boom, burned in 1924 with the

loss of four lives.

Oil field fires were all too common. One of the major oil field

fires destroyed oil storage tanks at the Brewer farm at Merriman,

and a number of employees of the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company

were killed. Before enclosed storage tanks were put in, oil was

moved from a well to an earthen tank usually via an open ditch. An

eyewitness recalled that about a hundred men were standing around

a well watching the oil moving through the ditch when a bystander

started to light a cigarette. Another bystander knocked the cigarette

and match from the would-be smoker’s hand, likely averting a major

tragedy.

It was extremely dangerous to smoke around an oil well. A group of

oil field workers erected a shanty away from the oil field where

they were working so they would have a safe place to smoke. They

put a sign on their shanty that read “the Ranger Country Klub.

CRIME - Like all other oil boomtowns, Ranger attracted criminals.

Gamblers, thieves, prostitutes, pimps, robbers, hoodlums, and all

other kinds of criminals arrived in Ranger eager to make quick

money and lots of it. Gunfights and murders were common: in one

24-hour period there were five murders. It was not uncommon to

see dead men sprawled in the street. It was said that the police

chief counted 66 “reported” murders and suicides in 1919—and

then gave up counting! A 1919 Ranger Daily Times had a news

item: “Police were so busy Sunday rounding up a gang of alleged

highwaymen that they had little time to devote to misdemeanors.”

Although the “wild West” was past, hip-holstered, gun-toting men

were common sights. Policing, always a potentially dangerous

occupation, was even more so during the boom.

A 1919 Ranger Daily Times article reported the killing of Alf

Jordan, member of the police force, by Bill Shamlin, who had

been under investigation in a $20,000 blackmail scheme and a

bootlegging operation and otherwise figuring prominently in

police records. In 1921 the Texas Rangers raided the Commercial

Hotel in Ranger. The hotel was widely known throughout the

area as a public gambling house and saloon. As a result of

that raid 87 gamblers were arrested, and eight gambling tables

and other gambling paraphernalia were seized. Sometime after

incorporation Ranger voted in a local option election to

outlaw liquor, but it continued to be available. In 1922

aroused citizens poured into the streets $16,000 worth of

liquor seized by the Texas Rangers in illegal bars & gambling

houses. The Rangers closed those places as well as houses of

ill repute and ran undesirables out of town. Various citizen

groups in Ranger continued to fight for rigid law enforcement,

and even the Ku Klux Klan, active in Ranger during the oil

boom, campaigned against what it described as “immorality

and continuing lawlessness.”

LAW ENFORCEMENT - Law

enforcement in Ranger

Camp Valley was in the

hands of the Texas

Rangers. They provided

protection against frequent

Indian raids and bandits

in sparsely settled com-

munities. Even after Ranger

had a police force, the

Texas Rangers continued to

be involved in resolving

some crimes, such as

LAW ENFORCEMENT - Law

enforcement in Ranger

Camp Valley was in the

hands of the Texas

Rangers. They provided

protection against frequent

Indian raids and bandits

in sparsely settled com-

munities. Even after Ranger

had a police force, the

Texas Rangers continued to

be involved in resolving

some crimes, such as

raiding gambling dens, brothels, and speakeasies, rounding

up their operators, and running them out of town.

Texas Rangers thwarted the only train robbery attempt in

Eastland County. In 1882 a robbery on an express train

was attempted while the train was in Ranger. Tipped off

about a possible robbery, Texas Rangers were aboard and

began shooting when they saw the robbers. In 1921 the

Rangers raided a gambling operation in the Commercial Hotel.

Texas Rangers would typically solve a crime and then would

leave town to go to another community that needed their

services. However, during the oil boom several Rangers were

stationed in Ranger. Local police were involved in some of

the same law enforcement as the Texas Rangers but were also

responsible for dealing with fights, drunken offenders,

general rowdiness, and other misdemeanors. Many citizens

felt that the police were not as rigorous in enforcing laws

as they should be, and the Ku Klux Klan, active in Ranger

during the oil boom, decried the continuing “immorality and

general lawlessness.”

Law enforcement often did indeed seem spotty. For example,

former Texas Ranger Byron Parrish, promising to rid Ranger

of “gambling, soliciting, wide-open cabarets, and gun-toting,”

was appointed chief-of-police in late 1919. Scarcely two

months after his appointment, city commissioners put him on

probation for failure to close gambling houses, and he was

eventually dismissed. Chiefs-of-police came and went with

some frequency in those days. The Ranger Daily Times reported

that there were 16 chiefs-of-police within 47 months, from

February 1919 to January 1923.

Law enforcement in Ranger as in other boomtowns could be

viewed ambiguously. If laws were enforced rigorously, then

certain entertainment and the income of those involved would

be adversely affected: for example, after local option,

speakeasies and nightclubs would theoretically be closed

for selling illegal liquor. However, if the police overlooked

these places, they could be accused of encouraging the growth

of organized crime. In oil boomtowns it was commonly thought,

sometimes with justification, that police were involved in

bribery and bootlegging.

HOTELS - In her

History of Eastland

County, Texas (Dallas,

A.D. Aldridge, 1904),

Mrs. George Langston

said that a Mr. Griffin

“did a thriving hotel

business” in a tent

beginning around 1880.

Another early hotel was

run by Mr. and Mrs.

John Bryant from

Illinois. They began

HOTELS - In her

History of Eastland

County, Texas (Dallas,

A.D. Aldridge, 1904),

Mrs. George Langston

said that a Mr. Griffin

“did a thriving hotel

business” in a tent

beginning around 1880.

Another early hotel was

run by Mr. and Mrs.

John Bryant from

Illinois. They began

serving meals under a tent but eventually built a two-story

hotel just east of the downtown area on what was then South

Front Street, later Highway 80. The Bryant Hotel (pictured

here) remained Ranger’s foremost hotel until the oil boom,

when the Bryants retired.

Ranger was ill prepared to deal with the masses of people

coming into town drawn by the oil boom. Hotels and rooming

houses sprang up, but they were inadequate to cope with the

influx. Men slept in hotel rooms in shifts, and they paid

to sleep in chairs in hotel lobbies. The scarcity of hotels

was common in oil boomtowns. In some, men not only slept in

shifts and paid to sleep in hotel lobby chairs but also slept

on cots in hotel hallways and paid to sleep in barber chairs.

John McCleskey, newly wealthy from the oil well that ushered

in Ranger’s oil boom, built the McCleskey Hotel, which opened

in 1918 (construction cost $32,000) & quickly became Ranger’s

pre-eminent hotel. Oil deals worth hundreds of thousands of

dollars were said to have been conducted in the McCleskey Hotel.

It became so popular that an annex eventually had to be built.

The annex was a tent, and clients slept on cots. The hotel

burned down in 1934. The Gholson Hotel, built by John Gholson,

opened in 1921. Another early major hotel was the Paramount

Hotel. The Little Jim Hotel catered to blacks but sold barbecue

to a wider clientele.

Buckley Paddock’s History of Texas: Fort Worth and the Texas

Northwest (Chicago, Lewis Publishing Company, 1922) said that

Ranger had 26 hotels (presumably about the time of the book’s

publication). By the early 1940’s there were three hotels,

according to an undated brochure issued by the Ranger Chamber

of Commerce. The same brochure reported twelve tourist courts

and four trailer parks. For years major hotels would publish

in the newspaper a list of their clients and where they were

from.

Just as today, hotels advertised to attract customers. The

Paramount Hotel, for example, advertised its “beautiful tile

baths, sensible rates, and air conditioning.” It noted that

the Paramount Coffee Shop was open 24 hours a day. It touted

the “hot biscuits, chicken and dumplings noon and night, and

juicy steaks.” The cooks were women, the ad said. Photo

courtesy of Ranger Historical Preservation Society

SOME EARLY CLUBS & OTHER ORGANIZATIONS - A number of clubs

and other organizations began before the oil boom, and still

more were founded after the boom. The 1903 Club, a women’s

literary club, was one of the early clubs. It developed into

the 1920 Club, which in turn spawned three other literary

and study clubs: the New Era, Junior New Era, and Columbia

Study Clubs. The motto of the 1920 Club was especially

poignant: “Knowledge comes, but wisdom lingers.”

The Masonic Lodge in Ranger was chartered in 1892. Among

other early clubs were the Lions, Rotary, Child Welfare Club,

Elks, Odd Fellows, and Rebekah Lodge. La Societé des Quarante

Hommes et Huit Chevaux (the Society of Forty Men and Eight

Horses) was a men’s social club.

Among its other civic accomplishments, the Rotary Club was

instrumental in organizing three Boy Scout troops in Ranger

in 1927. The Ivy Leaf Study Club was an auxiliary of the

Eastern Star. Ranger’s Parent-Teacher Association was

organized at Young School in 1919. The P.T.A. in turn

organized the Child Study Club, whose purpose was to study

and discuss the problems of the pre-school child.

Many of the early clubs and organizations made major con-

tributions to Ranger’s welfare. For example, the 1920 Club,

the New Era Club, and possibly others established student

loan funds. The Child Welfare Club, established in 1921,

helped place a health services nurse in the public schools,

raised funds to send handicapped children to children’s

hospitals for treatment, distributed milk to undernourished

children, and set up a day nursery. The work of the Club

over a several year period was so outstanding that its

accomplishments were recognized by the State Welfare Board

and at the national level. The Club’s slogan at Christmas-

time was: “No child in Ranger should go without clothing,

food or toys.”

The Carl Barnes Post No. 69 of the American Legion was

organized in 1923 & was involved in many civic improvements.

The Ranger Chamber of Commerce was organized in 1918 with

25 charter members. By late 1919, it had 300 members. The

Retail Merchants Association was founded in the early 1920s.

A Ranger unit of the Texas National Guard was organized in

1928.

KU KLUX KLAN - Ranger was the center of activity for the Ku

Klux Klan in Eastland County in the early twenties. The

first Klan movement had flourished during Reconstruction,

with chiefly Southern membership & concerns, but the second

Klan movement, which began in 1915, eventually had an almost

nationwide membership in its heyday in the early twenties.

It thrived on a wider range of concerns. Among these was

fear of immigrants, who were entering the country in large

numbers, of blacks, who were moving into cities in increasing

numbers, and of Jews and Catholics, who were rising in the

economic and social order.

The Klan said it stood for “100 per cent Americanism, for

the church, the home, the school, &d the purity of womanhood.”

This was typical pro-Klan propaganda: “Remember—Every

criminal, every gambler, every thug, every libertine, every

girl ruiner, every home wrecker, every wife beater, every

dope peddler, every moonshiner, every crooked politician,

every shyster lawyer, every white slaver, every brothel

madam, every controlled newspaper is fighting the Klan.

Think it over—which side are you on?”

For people in Ranger, it issued a statement: “We have set

our seal of disapproval on bootlegging, gambling, and

prostitution, and if those engaged in these lawless

occupations wish to live in Ranger, they must change

their occupation, for we never forget. The invisible

eye is upon them.”

The Klan began to have strong opposition. Ranger and

Eastland branches of the Good Government Club were formed.

In declaring their opposition to the Klan, the clubs

cited the United States Constitution on freedom and

equality and denounced the Klan for boycotting Catholic

and minority businesses.

There was great opposition to the Klan on the statewide

level and even a wider level. In their platforms for the

1924 election, Miriam A. (“Ma”) Ferguson and Dan Moody,

successfully campaigning for governor and attorney general

respectively, had strong anti-Klan positions. After that

election, the Klan declined rapidly. Soon it had virtually

disappeared from Ranger and the rest of Eastland County.

By the mid-twenties Texas had become one of the most anti-

Klan states of all. The third Klan movement emerged in

the mid-40’s, with chapters in many parts of the country

but mainly in the South, where its chief concern was civil

rights issue

MR. M.H. HAGAMAN - was one of the

central figures in Ranger’s early

history and a major contributor to

Ranger’s progress. He came to Ranger

in the late 1880’s to teach school and

then served as school superintendent

for two years before going into business.

Always a civic leader, he became Ranger’s

first mayor when the city incorporated in

1919. He worked tirelessly for civic

improvements. Some of the veterans of the

Ranger oil boom considered Hagaman and

John Gholson to be the two men who had

MR. M.H. HAGAMAN - was one of the

central figures in Ranger’s early

history and a major contributor to

Ranger’s progress. He came to Ranger

in the late 1880’s to teach school and

then served as school superintendent

for two years before going into business.

Always a civic leader, he became Ranger’s

first mayor when the city incorporated in

1919. He worked tirelessly for civic

improvements. Some of the veterans of the

Ranger oil boom considered Hagaman and

John Gholson to be the two men who had

done more for Ranger in its early years than anyone else.

When he resigned as school superintendent, he founded the

Hagaman Hardware and Farm Implement Company. He eventually

went into partnership with Bohning Brothers in an extensive

wholesale and retail mercantile business, Bohning-Hagaman

Company. After the Company dissolved partnership, Hagaman

went into farming and ranching.

After the oil boom began, he founded the Hagaman Refining

Company and the Hagaman Water Works Company. Hagaman

Lake, which he built on his ranch, became Ranger’s first

reliable water supply and remained its water supply until

the creation of Lake Leon, dedicated in 1955. A filtration

plant built at Hagaman Lake at the time it became Ranger’s

water supply could handle 600,000 gallons of water a day.

Hagaman gave the City permission to build a sewage treatment

plant on his ranch.

Matthew Hilsman Hagaman was born October 11, 1861 to John

and Catharine Hagaman in Johnston County, Tennessee. He

was a graduate of the University of Tennessee. He and his

wife, Emma Whittington Hagaman, had three children who

survived infancy: Leslie (husband of longtime Ranger

teacher Helen Hagaman), Ruth, and Fred.

M.H. Hagaman, a Democrat, served two terms in the Texas

House of Representatives from January 1925 to January 1929.

While in the Legislature, he served on a number of committees,

among them Appropriations; Banks and Banking; Commerce and

Manufactures (which he chaired one term); Oil, Gas, and

Mining; and Conservation and Reclamation.

Hagaman died September 8, 1949 and is buried in Evergreen

Cemetery. Photo courtesy of the author’s collection.

CIVIC IMPROVEMENTS - Ranger voted to incorporate February 4,

1919, and on February 19, the first city officers were elected.

A city charter was adopted. The new city government set about

confronting problems common to many newly incorporated areas.

Among these were providing for utilities, a sewer system, a

hospital, a reliable water supply, and paving of streets.

Ranger Water Works, under the guidance of M.H. Hagaman, Ranger’s

first mayor, built a pump station at Hagaman Lake & a distribution

system. The City reached an agreement with Texas & Pacific

Railroad whereby the City could use the railroad’s pipe line,

already laid, to bring water to the City limits. Eventually

a filtration plant was built to insure a dependable source of

good water. At the time of its completion in 1919, it could

handle 600,000 gallons of water a day.

In 1919 bonds were issued to build a sewer system and begin

paving streets. At that time, the paving contract was one

of the largest paving contracts ever signed in Texas. It

called for 67 blocks to be completed by 1921. By the end

of that year all the business district and many blocks in

residential areas had been paved. Like many other Texas

cities, Ranger used bricks from the Thurber Brick Company

for paving streets.

School trustees had anticipated an enrollment of 1,000 in

1918, but 1,350 students showed up. A bond election passed,

and eventually Cooper, Young, Hodges Oak Park, and Tiffin

elementary school buildings were built. An elementary

school building was built at Merriman, not from bond funds

but rather from the school’s share of the royalties from

the Wagner No. 1 oil well built on the school property.

Tiffin and Merriman were not originally part of the Ranger

Independent School District. Still another bond issue was

passed in the early 1930’s for construction of the building

that eventually came to be called the recreation building.

Brick for that building came from the Tiffin elementary

school building, torn down in 1933.

Health care was a major concern, especially in light of

the 1918 flu epidemic that killed many people in Ranger and

throughout the country. Ranger’s first hospital, Ranger

General Hospital, opened in 1919 just south of Blundell

Street near Strawn Road. It had problems from the beginning,

including a lack of running water, inadequate sewage disposal,

and problems with electricity. Plans for a new hospital

began in 1920, but it was not until 1924 that a new hospital,

called Ranger City-County Hospital (also called Ranger

General Hospital) opened.

JOHN McCLESKEY - Oil was discovered on

John McCleskey’s farm about a mile south

of downtown Ranger on October 17, 1917.

The McCleskey well ushered in Ranger’s

oil boom. John McCleskey—farmer, cattleman,

bricklayer, and oilman--used part of his

newly found wealth to build the McCleskey

Hotel. It became the site of many deals

involving oil and oil leases, many worth

hundreds of thousands of dollars. John

was a skilled bricklayer in addition to

being a farmer and cattleman, and, always

thrifty, he helped mix the mortar when

JOHN McCLESKEY - Oil was discovered on

John McCleskey’s farm about a mile south

of downtown Ranger on October 17, 1917.

The McCleskey well ushered in Ranger’s

oil boom. John McCleskey—farmer, cattleman,

bricklayer, and oilman--used part of his

newly found wealth to build the McCleskey

Hotel. It became the site of many deals

involving oil and oil leases, many worth

hundreds of thousands of dollars. John

was a skilled bricklayer in addition to

being a farmer and cattleman, and, always

thrifty, he helped mix the mortar when

construction began on his hotel.

It was said that Mrs. McCleskey became very angry when the oil

from the McCleskey well splattered her Leghorn chickens! Another

story, also quite likely apocryphal, was that she was asked what

she would do first with her new wealth. She replied that she

would buy a new ax. Scholars who have studied the folklore of

the oil field have said that the ax story and other such stories

involving the purchase of a relatively inexpensive item in the

wake of new wealth were very common.

John Rust, one of the interviewees in the Oral History of the

Texas Oil Industry (Dolph Briscoe Center for American History,

University of Texas) was living on a farm adjacent to the

McCleskeys’ farm when the discovery oil well came in. When

he heard the ax story, he said that he doubted it. He said

that Mrs. McCleskey would not have needed a new ax! Rust said

that if she mentioned getting a new ax, she was jesting.

John Hill McCleskey was born in Oakwood, Hall County, Georgia

September 24, 1854, the son of John L. and Emily McCleskey. As

a young man (some sources say he was 16 years old) he moved

to Fort Worth, where he farmed, raised livestock, and worked

with horses. In 1889 he moved to Ranger, settling on the farm

that became the site of the Ranger oil boom inaugural well. He

and his first wife, who preceded him in death, had four children

that survived infancy: Mary Emma, William Lafayette, John Tillman,

and George Hill.

John McCleskey did not live to see the completion of his hotel

or to enjoy his new wealth for very long. He was recovering

from typhoid fever when he developed massive indigestion from

eating some peaches and had a relapse. He died July 19, 1918.

He is buried in Merriman Cemetery.

MOVIE THEATERS - In his book Lone Star Picture Shows (Texas A&M

University Press, 2001), Richard Schroeder points out that when

a Dallas audience in 1897 viewed the first motion picture ever

shown in Texas, Texans began a love affair with the movies.

Thomas Edison is credited with inventing the motion picture,

but it took contributions from innovators in chemistry, physics,

photography, and mechanical technology to bring his invention

to the point where it swept the nation in the early twentieth

century. Many towns and cities soon had motion picture venues

ranging from basic picture show theaters to so-called movie

palaces.

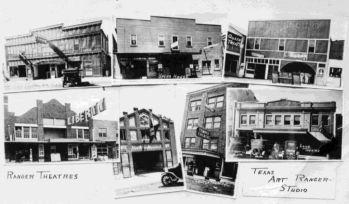

By 1920 Ranger had several theaters. The accompanying picture

shows seven of them: clockwise, from top left, the Hippodrome,

Opera House, Queen, Liberty (earlier called the Majestic and

pictured here in its original building), Lone Star (later called

the Columbia), Temple (later the Tower Theater), and Lamb Theater.

Other early theaters were the Eastside, Elite, Manhattan, and

Texas Theaters. The Rex Theater opened in 1922 in what was

described as the “old Liberty Theater building.”

The Liberty Theater and possibly some others not only showed

motion pictures but also hosted vaudeville performances. In

light of the devastating April 6, 1919 fire that destroyed

several blocks, an ad for the Liberty Theater in September

of that year claimed that it was fireproof At least two

theaters burned down in the 1919 and 1920 fires: an earlier

theater called the Majestic burned down in the 1919 fire,

and the Queen Theater burned down in 1920.

When the Lone Star Theater opened, it advertised that it

had the latest in projection equipment and a silver screen.

It promised “absolutely no eyestrain even in the front seats

and a rock-steady picture.” It also had a specially con-

structed organ, used to accompany the movie before “talkies.”

Ventilation was said to be perfect, making it unnecessary to

bring a fan. A 1934 ad for the Columbia Theater said that

children under the age of 12 could see the first episode of

“The Perils of Pauline” for a nickel.

Theater managers had their share of problems: a 1919 news

article said that the managers of the Liberty and Lone Star

Theaters had pleaded guilty to running Sunday shows in vio-

lation of state law and were assessed the minimum fine of

$20 each.

The Arcadia Theater, which replaced the Lamb Theater in 1929

after the latter was razed, had a pipe organ but showed only

talkies. The Arcadia was described as the most lavish movie

theater between Fort Worth and Abilene. Unlike most of the

earlier theaters, it had upholstered seats, deep carpets,

and velvet curtains. In 1942 owner and manager Brann Garner

put a large radio on the stage so that theatergoers could

hear at least one and possibly more of President Franklin

Roosevelt’s “Fireside Chats.” The Arcadia burned down in

1952. The Tower Theater had burned down earlier, and with

it and the Arcadia both gone, downtown Ranger was left with

no movie theaters.

Ranger’s only drive-in theater opened sometime in the early

1950’s and operated until sometime in the mid 1980’s.

Friday 13th, 2016 was a GOOD day for the Ranger Historical

Preservation Society. Phone rang at 9:19 AM and the voice

on the other end said - “is this the historical society?”

Of course the answer was yes - then “do you own those two

buildings on Austin Street...what do you plan to do with

them...?”

The decrepit buildings that stood in late 2016 was transformed

into a jewel for the City of Ranger. Photos were sent to the

Waggin’ Tongue on the progress of the remodel of the building

that was known as the Cole Apartments Upstairs and a restaurant

at ground level (Building on Left) and the Lone Star Theatre

(Building on Right). Eventually, those two building were

remodeled and in operation for a period of time.

MOVIE THEATERS - In his book Lone Star Picture Shows (Texas A&M

University Press, 2001), Richard Schroeder points out that when

a Dallas audience in 1897 viewed the first motion picture ever

shown in Texas, Texans began a love affair with the movies.

Thomas Edison is credited with inventing the motion picture,

but it took contributions from innovators in chemistry, physics,

photography, and mechanical technology to bring his invention

to the point where it swept the nation in the early twentieth

century. Many towns and cities soon had motion picture venues

ranging from basic picture show theaters to so-called movie

palaces.

By 1920 Ranger had several theaters. The accompanying picture

shows seven of them: clockwise, from top left, the Hippodrome,

Opera House, Queen, Liberty (earlier called the Majestic and

pictured here in its original building), Lone Star (later called

the Columbia), Temple (later the Tower Theater), and Lamb Theater.

Other early theaters were the Eastside, Elite, Manhattan, and

Texas Theaters. The Rex Theater opened in 1922 in what was

described as the “old Liberty Theater building.”

The Liberty Theater and possibly some others not only showed

motion pictures but also hosted vaudeville performances. In

light of the devastating April 6, 1919 fire that destroyed

several blocks, an ad for the Liberty Theater in September

of that year claimed that it was fireproof At least two

theaters burned down in the 1919 and 1920 fires: an earlier

theater called the Majestic burned down in the 1919 fire,

and the Queen Theater burned down in 1920.

When the Lone Star Theater opened, it advertised that it

had the latest in projection equipment and a silver screen.

It promised “absolutely no eyestrain even in the front seats

and a rock-steady picture.” It also had a specially con-

structed organ, used to accompany the movie before “talkies.”

Ventilation was said to be perfect, making it unnecessary to

bring a fan. A 1934 ad for the Columbia Theater said that

children under the age of 12 could see the first episode of

“The Perils of Pauline” for a nickel.

Theater managers had their share of problems: a 1919 news

article said that the managers of the Liberty and Lone Star

Theaters had pleaded guilty to running Sunday shows in vio-

lation of state law and were assessed the minimum fine of

$20 each.

The Arcadia Theater, which replaced the Lamb Theater in 1929

after the latter was razed, had a pipe organ but showed only

talkies. The Arcadia was described as the most lavish movie

theater between Fort Worth and Abilene. Unlike most of the

earlier theaters, it had upholstered seats, deep carpets,

and velvet curtains. In 1942 owner and manager Brann Garner

put a large radio on the stage so that theatergoers could

hear at least one and possibly more of President Franklin

Roosevelt’s “Fireside Chats.” The Arcadia burned down in

1952. The Tower Theater had burned down earlier, and with

it and the Arcadia both gone, downtown Ranger was left with

no movie theaters.

Ranger’s only drive-in theater opened sometime in the early

1950’s and operated until sometime in the mid 1980’s.

Friday 13th, 2016 was a GOOD day for the Ranger Historical

Preservation Society. Phone rang at 9:19 AM and the voice

on the other end said - “is this the historical society?”

Of course the answer was yes - then “do you own those two

buildings on Austin Street...what do you plan to do with

them...?”

The decrepit buildings that stood in late 2016 was transformed

into a jewel for the City of Ranger. Photos were sent to the

Waggin’ Tongue on the progress of the remodel of the building

that was known as the Cole Apartments Upstairs and a restaurant

at ground level (Building on Left) and the Lone Star Theatre

(Building on Right). Eventually, those two building were

remodeled and in operation for a period of time.

The vision of one young man and the RHPS changed these two

buildings, pictured above, to what they are today. The buildings

were donated to Chad Cunningham, with the stipulation, the

front of the buildings must remain as close to the original

as possible. Mr. Cunningham agreed and the work began.

In May 2016, The Lone Star Theatre Bar held an eventful grand

opening. The first event held was the 95th birthday party

for Mrs. Dorothy Anderson; a private family lunch with live

music, dancing and entertainment on May 14th. Although the

buildings now stand empty with a lack of patrons, the up-

stairs living area is occupied. Many still have the hope that

someone will see this “little jewel” and bring a business back

to Ranger but in the meantime someone is paying property taxes.

The vision of one young man and the RHPS changed these two

buildings, pictured above, to what they are today. The buildings

were donated to Chad Cunningham, with the stipulation, the

front of the buildings must remain as close to the original

as possible. Mr. Cunningham agreed and the work began.

In May 2016, The Lone Star Theatre Bar held an eventful grand

opening. The first event held was the 95th birthday party

for Mrs. Dorothy Anderson; a private family lunch with live

music, dancing and entertainment on May 14th. Although the

buildings now stand empty with a lack of patrons, the up-

stairs living area is occupied. Many still have the hope that

someone will see this “little jewel” and bring a business back

to Ranger but in the meantime someone is paying property taxes.

EARLY SCHOOLS - The first school building in the new town of Ranger

was a one-room frame schoolhouse built in 1880 on the site where

the high school was for many years. A private school, the Ray

Academy, operated in Ranger in the late 1890’s. Like some other

schools of the time, private or public, it was rather strict:

boys and girls were taught in separate classes. In the early-

to-mid 1880’s, a teacher’s salary of $60 a month was considered

especially generous. Opening in time for the 1886/87 school

year, the two-story frame building pictured here served all

grades until 1907, when a one-room building was built for primary

grade students. A two-story brick building was constructed in

1905 under the leadership of superintendent J. E. Temple Peters.

It served high school students until a new building opened in

1923. The senior class of 1977 was the last class to graduate

from that building. Walter Prescott Webb, a graduate of Ranger

High School before going on to a teaching career, including a

professorship at the University of Texas, recalled those early

high school classes many years later. They were, he said, a

mixture of the most unsophisticated country kids one could imagine

and sophisticated city kids: boys who knew how to wear a white

collar and the most charming girls, with bows in their hair and

buckles on their shoes. M.H. Hagaman, who had come to Ranger

to teach, was school superintendent in the late 1880’s. He

recalled that in 1889 there were about 150 students and three

teachers. The high school in those days served not only Ranger

students but also some from out of town. These students came

to Ranger because, in Hagaman’s words, it had a good high school

for that day. They boarded with local families.

HISTORY OF RANGER - Page 1

ARTICLES TO CONTINUE MONTHLY

EARLY SCHOOLS - The first school building in the new town of Ranger

was a one-room frame schoolhouse built in 1880 on the site where

the high school was for many years. A private school, the Ray

Academy, operated in Ranger in the late 1890’s. Like some other

schools of the time, private or public, it was rather strict:

boys and girls were taught in separate classes. In the early-

to-mid 1880’s, a teacher’s salary of $60 a month was considered

especially generous. Opening in time for the 1886/87 school

year, the two-story frame building pictured here served all

grades until 1907, when a one-room building was built for primary

grade students. A two-story brick building was constructed in

1905 under the leadership of superintendent J. E. Temple Peters.

It served high school students until a new building opened in

1923. The senior class of 1977 was the last class to graduate

from that building. Walter Prescott Webb, a graduate of Ranger

High School before going on to a teaching career, including a

professorship at the University of Texas, recalled those early

high school classes many years later. They were, he said, a

mixture of the most unsophisticated country kids one could imagine

and sophisticated city kids: boys who knew how to wear a white

collar and the most charming girls, with bows in their hair and

buckles on their shoes. M.H. Hagaman, who had come to Ranger

to teach, was school superintendent in the late 1880’s. He

recalled that in 1889 there were about 150 students and three

teachers. The high school in those days served not only Ranger

students but also some from out of town. These students came

to Ranger because, in Hagaman’s words, it had a good high school

for that day. They boarded with local families.

HISTORY OF RANGER - Page 1

ARTICLES TO CONTINUE MONTHLY

EARLY WATER SOURCES - The lack of a dependable source of water was a major problem confronting the new settlement of Ranger. One of the first attempts at solving the problem was a well dug in the middle of Locust Street (later called Main Street) about half a block west of the present intersection of Main & Commerce Streets.

FIRE - Ranger had little fire protection in the early days, especially before there was a reliable municipal water supply. Before the city incorporated in 1919 and got what was at the time considered modern fire- fighting equipment, fire- fighting was done by volunteers, often in bucket brigades. Sometimes fire-

LAW ENFORCEMENT - Law enforcement in Ranger Camp Valley was in the hands of the Texas Rangers. They provided protection against frequent Indian raids and bandits in sparsely settled com- munities. Even after Ranger had a police force, the Texas Rangers continued to be involved in resolving some crimes, such as

HOTELS - In her History of Eastland County, Texas (Dallas, A.D. Aldridge, 1904), Mrs. George Langston said that a Mr. Griffin “did a thriving hotel business” in a tent beginning around 1880. Another early hotel was run by Mr. and Mrs. John Bryant from Illinois. They began

MR. M.H. HAGAMAN - was one of the central figures in Ranger’s early history and a major contributor to Ranger’s progress. He came to Ranger in the late 1880’s to teach school and then served as school superintendent for two years before going into business. Always a civic leader, he became Ranger’s first mayor when the city incorporated in 1919. He worked tirelessly for civic improvements. Some of the veterans of the Ranger oil boom considered Hagaman and John Gholson to be the two men who had

JOHN McCLESKEY - Oil was discovered on John McCleskey’s farm about a mile south of downtown Ranger on October 17, 1917. The McCleskey well ushered in Ranger’s oil boom. John McCleskey—farmer, cattleman, bricklayer, and oilman--used part of his newly found wealth to build the McCleskey Hotel. It became the site of many deals involving oil and oil leases, many worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. John was a skilled bricklayer in addition to being a farmer and cattleman, and, always thrifty, he helped mix the mortar when

MOVIE THEATERS - In his book Lone Star Picture Shows (Texas A&M University Press, 2001), Richard Schroeder points out that when a Dallas audience in 1897 viewed the first motion picture ever shown in Texas, Texans began a love affair with the movies. Thomas Edison is credited with inventing the motion picture, but it took contributions from innovators in chemistry, physics, photography, and mechanical technology to bring his invention to the point where it swept the nation in the early twentieth century. Many towns and cities soon had motion picture venues ranging from basic picture show theaters to so-called movie palaces. By 1920 Ranger had several theaters. The accompanying picture shows seven of them: clockwise, from top left, the Hippodrome, Opera House, Queen, Liberty (earlier called the Majestic and pictured here in its original building), Lone Star (later called the Columbia), Temple (later the Tower Theater), and Lamb Theater. Other early theaters were the Eastside, Elite, Manhattan, and Texas Theaters. The Rex Theater opened in 1922 in what was described as the “old Liberty Theater building.” The Liberty Theater and possibly some others not only showed motion pictures but also hosted vaudeville performances. In light of the devastating April 6, 1919 fire that destroyed several blocks, an ad for the Liberty Theater in September of that year claimed that it was fireproof At least two theaters burned down in the 1919 and 1920 fires: an earlier theater called the Majestic burned down in the 1919 fire, and the Queen Theater burned down in 1920. When the Lone Star Theater opened, it advertised that it had the latest in projection equipment and a silver screen. It promised “absolutely no eyestrain even in the front seats and a rock-steady picture.” It also had a specially con- structed organ, used to accompany the movie before “talkies.” Ventilation was said to be perfect, making it unnecessary to bring a fan. A 1934 ad for the Columbia Theater said that children under the age of 12 could see the first episode of “The Perils of Pauline” for a nickel. Theater managers had their share of problems: a 1919 news article said that the managers of the Liberty and Lone Star Theaters had pleaded guilty to running Sunday shows in vio- lation of state law and were assessed the minimum fine of $20 each. The Arcadia Theater, which replaced the Lamb Theater in 1929 after the latter was razed, had a pipe organ but showed only talkies. The Arcadia was described as the most lavish movie theater between Fort Worth and Abilene. Unlike most of the earlier theaters, it had upholstered seats, deep carpets, and velvet curtains. In 1942 owner and manager Brann Garner put a large radio on the stage so that theatergoers could hear at least one and possibly more of President Franklin Roosevelt’s “Fireside Chats.” The Arcadia burned down in 1952. The Tower Theater had burned down earlier, and with it and the Arcadia both gone, downtown Ranger was left with no movie theaters. Ranger’s only drive-in theater opened sometime in the early 1950’s and operated until sometime in the mid 1980’s. Friday 13th, 2016 was a GOOD day for the Ranger Historical Preservation Society. Phone rang at 9:19 AM and the voice on the other end said - “is this the historical society?” Of course the answer was yes - then “do you own those two buildings on Austin Street...what do you plan to do with them...?” The decrepit buildings that stood in late 2016 was transformed into a jewel for the City of Ranger. Photos were sent to the Waggin’ Tongue on the progress of the remodel of the building that was known as the Cole Apartments Upstairs and a restaurant at ground level (Building on Left) and the Lone Star Theatre (Building on Right). Eventually, those two building were remodeled and in operation for a period of time.

The vision of one young man and the RHPS changed these two buildings, pictured above, to what they are today. The buildings were donated to Chad Cunningham, with the stipulation, the front of the buildings must remain as close to the original as possible. Mr. Cunningham agreed and the work began. In May 2016, The Lone Star Theatre Bar held an eventful grand opening. The first event held was the 95th birthday party for Mrs. Dorothy Anderson; a private family lunch with live music, dancing and entertainment on May 14th. Although the buildings now stand empty with a lack of patrons, the up- stairs living area is occupied. Many still have the hope that someone will see this “little jewel” and bring a business back to Ranger but in the meantime someone is paying property taxes.

EARLY SCHOOLS - The first school building in the new town of Ranger was a one-room frame schoolhouse built in 1880 on the site where the high school was for many years. A private school, the Ray Academy, operated in Ranger in the late 1890’s. Like some other schools of the time, private or public, it was rather strict: boys and girls were taught in separate classes. In the early- to-mid 1880’s, a teacher’s salary of $60 a month was considered especially generous. Opening in time for the 1886/87 school year, the two-story frame building pictured here served all grades until 1907, when a one-room building was built for primary grade students. A two-story brick building was constructed in 1905 under the leadership of superintendent J. E. Temple Peters. It served high school students until a new building opened in 1923. The senior class of 1977 was the last class to graduate from that building. Walter Prescott Webb, a graduate of Ranger High School before going on to a teaching career, including a professorship at the University of Texas, recalled those early high school classes many years later. They were, he said, a mixture of the most unsophisticated country kids one could imagine and sophisticated city kids: boys who knew how to wear a white collar and the most charming girls, with bows in their hair and buckles on their shoes. M.H. Hagaman, who had come to Ranger to teach, was school superintendent in the late 1880’s. He recalled that in 1889 there were about 150 students and three teachers. The high school in those days served not only Ranger students but also some from out of town. These students came to Ranger because, in Hagaman’s words, it had a good high school for that day. They boarded with local families. HISTORY OF RANGER - Page 1 ARTICLES TO CONTINUE MONTHLY