Articles - Page 3:

FAMOUS VISITORS POST OFFICE BOYCE HOUSE

EARLY NEWSPAPERS W.K. GORDON SHOOTING AN OIL WELL

TICKVILLE BAND ST. RITA'S T&P RAILWAY CO.

RANGER'S HOSPITAL JAKE HAMON RAILROAD JOHN GHOLSON

FAMOUS VISITORS - Ranger had a steady stream of visitors during the

oil boom and for years thereafter. Among them were the famous, the

not-famous—and the infamous. In the latter group were Bonnie & Clyde,

of the Clyde Barrow gang, who “visited” the Ranger National Guard

Armory in February 1934, helping themselves to an arsenal of weapons.

However, that’s another story… One of the early famous visitors was

United States Ex-President William Howard Taft. Elected President

in 1908, he failed to be re-elected in 1912, yielding the Presidency

to Woodrow Wilson. Taft became a professor of law at Yale University

after leaving the White House and, after several other Government

positions, was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1921.

Before he began serving on the Supreme Court, he visited Ranger. Before

the Former Presidents Act of 1958, the United States Secret Service

did not provide protection for former Presidents, so Taft mingled

with the crowds on the streets of Ranger unprotected and unnoticed.

So far as is known, his only official appearance in Ranger was before

the newly organized 1920 Club, a women’s study club. One Club member

wrote on her 1920/1921 year book that Club members had to hunt for

the piano music to “Hail to the Chief” so that their guest speaker

could be properly welcomed!

Rex Beach, prolific American novelist and playwright (as well as

Olympic water polo player), visited Ranger during the oil boom to

do research for his novel, Flowing Gold. Published in 1922, it

was made into a movie directed by Alfred E. Green and produced by

Warner Brothers in 1940. It is set in American oilfields in general

and not specifically the Ranger oilfield. After years of unsuccessful

prospecting for gold, Beach had turned to writing. Most of his novels,

like Flowing Gold, are adventure stories, and many were made into

movies.

Billy Sunday, the best known and most influential American evangelist

in the first two decades of the twentieth century, visited Ranger during

the oil boom, preaching to large crowds in the streets. At the time of

his Ranger visit, he was attracting the largest crowds of any evangelist.

He was especially well known for his strong support of Prohibition. His

preaching possibly was a strong factor in the passage of the Eighteenth

Amendment in 1919, which outlawed alcoholic beverages in the United States.

Aviatrix Amelia Earhart landed her Pitcairn Autogiro plane (pictured above)

in Ranger June 16, 1931 to refuel. The newspaper headline read: “Miss

Earhart Lands Windmill in Ranger.” Her stop had not been announced, but

a large crowd gathered while the Lone Star Gas Company supplied 30 gallons

of gasoline. She told observers that her plane’s highest speed was 110

miles an hour, with a cruising speed of 80 miles an hour. She said that

at $15,000 it was expensive because it was handmade. Six years after her

Ranger refueling stop, on July 2, 1937, while she and her navigator Fred

Noonan were making a round-the-world attempt, her plane, a Lockheed Electra,

disappeared in the Pacific, creating an as yet unsolved mystery.

FAMOUS VISITORS - Ranger had a steady stream of visitors during the

oil boom and for years thereafter. Among them were the famous, the

not-famous—and the infamous. In the latter group were Bonnie & Clyde,

of the Clyde Barrow gang, who “visited” the Ranger National Guard

Armory in February 1934, helping themselves to an arsenal of weapons.

However, that’s another story… One of the early famous visitors was

United States Ex-President William Howard Taft. Elected President

in 1908, he failed to be re-elected in 1912, yielding the Presidency

to Woodrow Wilson. Taft became a professor of law at Yale University

after leaving the White House and, after several other Government

positions, was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1921.

Before he began serving on the Supreme Court, he visited Ranger. Before

the Former Presidents Act of 1958, the United States Secret Service

did not provide protection for former Presidents, so Taft mingled

with the crowds on the streets of Ranger unprotected and unnoticed.

So far as is known, his only official appearance in Ranger was before

the newly organized 1920 Club, a women’s study club. One Club member

wrote on her 1920/1921 year book that Club members had to hunt for

the piano music to “Hail to the Chief” so that their guest speaker

could be properly welcomed!

Rex Beach, prolific American novelist and playwright (as well as

Olympic water polo player), visited Ranger during the oil boom to

do research for his novel, Flowing Gold. Published in 1922, it

was made into a movie directed by Alfred E. Green and produced by

Warner Brothers in 1940. It is set in American oilfields in general

and not specifically the Ranger oilfield. After years of unsuccessful

prospecting for gold, Beach had turned to writing. Most of his novels,

like Flowing Gold, are adventure stories, and many were made into

movies.

Billy Sunday, the best known and most influential American evangelist

in the first two decades of the twentieth century, visited Ranger during

the oil boom, preaching to large crowds in the streets. At the time of

his Ranger visit, he was attracting the largest crowds of any evangelist.

He was especially well known for his strong support of Prohibition. His

preaching possibly was a strong factor in the passage of the Eighteenth

Amendment in 1919, which outlawed alcoholic beverages in the United States.

Aviatrix Amelia Earhart landed her Pitcairn Autogiro plane (pictured above)

in Ranger June 16, 1931 to refuel. The newspaper headline read: “Miss

Earhart Lands Windmill in Ranger.” Her stop had not been announced, but

a large crowd gathered while the Lone Star Gas Company supplied 30 gallons

of gasoline. She told observers that her plane’s highest speed was 110

miles an hour, with a cruising speed of 80 miles an hour. She said that

at $15,000 it was expensive because it was handmade. Six years after her

Ranger refueling stop, on July 2, 1937, while she and her navigator Fred

Noonan were making a round-the-world attempt, her plane, a Lockheed Electra,

disappeared in the Pacific, creating an as yet unsolved mystery.

POST OFFICE - The railroad reached Ranger on October 15, 1880, and the

train depot served briefly as the post office before a post office was

formally established December 27, 1880. James M. Davis, the first

postmaster, kept the post office in his store, J. M. Davis and Bros.,

located in a small frame building on Main Street near the northwest

corner of Main and Commerce Streets.

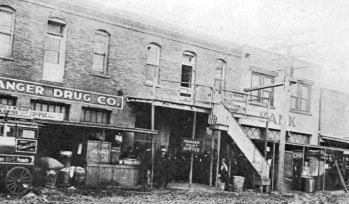

At some point before the oil boom the post office moved to the south

side of Main Street into a building that had earlier been occupied by

the Albert S. Riddle store and, on the second floor, by an early Ranger

newspaper, The Ranger Success. This building was in a row of buildings

occupied years later by C. E. May Insurance, Greer’s Western Wear, and

the Corner Drug Store. Pictured above is the post office in this location.

Before the oil boom the post office was adequate for Ranger and adjacent

rural areas. That changed quickly with the oil boom. For example,

during the second quarter of 1897, the post office issued 157 money

orders. In the last quarter of 1918, it issued 4,443 money orders. There

were often long lines, stretching for blocks, of people waiting to get

to the general delivery window. A Ranger Daily Times article reported

that enterprising young men would often arrive at the post office early

in the morning and then volunteer to sell their place in line to the

highest bidder.

The chamber of commerce began documenting the inadequacy of the mail

system during the oil boom. It presented statistics of receipts to the

postal authorities, and ultimately a new building was authorized. The

new frame building opened on North Marston Street in 1919. That year

the Post Office Department agreed to waive its requirement of paved

streets for city delivery. That and the chamber of commerce’s agreement

to name all streets and assign numbers to all houses greatly aided in

mail delivery.

Little more than a year later, in 1920, the post office moved again,

this time to an even larger building at Elm and Rusk Streets. The

Ranger post office had been promised four carriers, but the chamber

of commerce discovered that no one wanted to work for a carrier’s

salary of $100 a month, when many oilfield jobs paid more. The chamber

of commerce authorized a supplement of $25 for each carrier’s salary in

an effort to attract employees.

Plans for a new post office to replace the one at Elm and Rusk Streets

were announced in 1934, with $80,000 in government funds set aside for

construction. The cornerstone of the new post office was unveiled in

October 1937 as part of the celebration of the twentieth anniversary of

the discovery of oil. The building, Ranger’s current post office, opened

in January 1938 at the corner of North Austin and Walnut Streets.

During the 1930’s and early 1940’s many murals were commissioned in

public buildings across the economically depressed United States as an

effort to employ artists. The Works Progress Administration’s Federal

Art Project and other similar initiatives such as the Section of Fine

Arts of the U. S. Treasury Department spearheaded these efforts. Emil

Bisttram, a Hungarian-born artist, painted a mural, The Crossroads Town,

in the Ranger post office in the latter program. The mural purports to

depict Ranger as it was before the oil boom.

POST OFFICE - The railroad reached Ranger on October 15, 1880, and the

train depot served briefly as the post office before a post office was

formally established December 27, 1880. James M. Davis, the first

postmaster, kept the post office in his store, J. M. Davis and Bros.,

located in a small frame building on Main Street near the northwest

corner of Main and Commerce Streets.

At some point before the oil boom the post office moved to the south

side of Main Street into a building that had earlier been occupied by

the Albert S. Riddle store and, on the second floor, by an early Ranger

newspaper, The Ranger Success. This building was in a row of buildings

occupied years later by C. E. May Insurance, Greer’s Western Wear, and

the Corner Drug Store. Pictured above is the post office in this location.

Before the oil boom the post office was adequate for Ranger and adjacent

rural areas. That changed quickly with the oil boom. For example,

during the second quarter of 1897, the post office issued 157 money

orders. In the last quarter of 1918, it issued 4,443 money orders. There

were often long lines, stretching for blocks, of people waiting to get

to the general delivery window. A Ranger Daily Times article reported

that enterprising young men would often arrive at the post office early

in the morning and then volunteer to sell their place in line to the

highest bidder.

The chamber of commerce began documenting the inadequacy of the mail

system during the oil boom. It presented statistics of receipts to the

postal authorities, and ultimately a new building was authorized. The

new frame building opened on North Marston Street in 1919. That year

the Post Office Department agreed to waive its requirement of paved

streets for city delivery. That and the chamber of commerce’s agreement

to name all streets and assign numbers to all houses greatly aided in

mail delivery.

Little more than a year later, in 1920, the post office moved again,

this time to an even larger building at Elm and Rusk Streets. The

Ranger post office had been promised four carriers, but the chamber

of commerce discovered that no one wanted to work for a carrier’s

salary of $100 a month, when many oilfield jobs paid more. The chamber

of commerce authorized a supplement of $25 for each carrier’s salary in

an effort to attract employees.

Plans for a new post office to replace the one at Elm and Rusk Streets

were announced in 1934, with $80,000 in government funds set aside for

construction. The cornerstone of the new post office was unveiled in

October 1937 as part of the celebration of the twentieth anniversary of

the discovery of oil. The building, Ranger’s current post office, opened

in January 1938 at the corner of North Austin and Walnut Streets.

During the 1930’s and early 1940’s many murals were commissioned in

public buildings across the economically depressed United States as an

effort to employ artists. The Works Progress Administration’s Federal

Art Project and other similar initiatives such as the Section of Fine

Arts of the U. S. Treasury Department spearheaded these efforts. Emil

Bisttram, a Hungarian-born artist, painted a mural, The Crossroads Town,

in the Ranger post office in the latter program. The mural purports to

depict Ranger as it was before the oil boom.

BOYCE HOUSE - was an early reporter/editor of The

Ranger Daily Times and worked for other newspapers,

including ones in Eastland, Cisco, Olney, Brady,

and Fort Worth. He wrote a syndicated column,

articles, poems, and books on oil boomtowns,

including Ranger. In his work as a newspaperman

he became known for his hard work and integrity.

House was born on November 29,1896 in Piggott,

Arkansas, the son of Noah E. and Margaret (O’Brien)

House. Apparently because of his family’s financial

circumstances, he was unable to go to college. Instead

he went into journalism, one of his father’s occupations.

BOYCE HOUSE - was an early reporter/editor of The

Ranger Daily Times and worked for other newspapers,

including ones in Eastland, Cisco, Olney, Brady,

and Fort Worth. He wrote a syndicated column,

articles, poems, and books on oil boomtowns,

including Ranger. In his work as a newspaperman

he became known for his hard work and integrity.

House was born on November 29,1896 in Piggott,

Arkansas, the son of Noah E. and Margaret (O’Brien)

House. Apparently because of his family’s financial

circumstances, he was unable to go to college. Instead

he went into journalism, one of his father’s occupations.

House worked for a few years on the staffs of two Memphis, Tennessee

newspapers and then became editor/owner of the Piggott Banner. He

moved to Texas in 1920 and remained there the rest of his life. He

married Golda Fay Jamison in 1927. They had no children.

His two books most closely associated with Ranger are Were You in

Ranger? (Dallas, Tardy Publishing Co., 1935) and Roaring Ranger,

the World’s Biggest Boom (San Antonio, Naylor Co., 1951). Were

You in Ranger? was reprinted in 1999 by the Ranger Historical

Preservation Society. The Society’s reprint provides an index

and early-day and oil-boom-era photographs of Ranger. Because

of his knowledge of Texas oilfield towns, Metro-Goldwyn Mayer

invited House to Hollywood to serve as a technical consultant

for its film “Boom Town.” The biggest hit of 1940, “Boom Town”

starred Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy, Claudette Colbert, and Hedy

Lamarr. House had anticipated that this assignment would take

two weeks, but he ended up staying four months.

“Boom Town” takes place in a number of oilfield towns and not

specifically Ranger. In the trial scene toward the end of the

movie, Square John Sand, the character played by Spencer Tracy,

makes an impassioned speech extolling the wildcatter for his role

in opening up the country to oil exploration and production. House

wrote most of that speech, which he said might have been his

greatest contribution to the film.

Returning to Texas, House resumed his newspaper work and other

writing. His syndicated column, “I Give You Texas,” (originally

called “In the Shadow of the Capitol”) was published from 1938

to 1960. The column appeared in over a hundred newspapers.

Among his other writings were Tall Talk from Texas (San Antonio,

Naylor Co., 1944), Oil Field Fury (San Antonio, Naylor Co., 1954)

and collections of his poems. A weekly radio show further

enhanced his reputation both in Texas and nationally. He ran

unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor twice. House’s last

positions were with the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and the Texas

Credit Association. He died in Fort Worth December 30, 1961.

The Texas State Historical Association’s New Handbook of Texas

offers an assessment of House’s career: “He was a powerful

writer and could capture dramatic, spectacular, and moving

events on paper.”

J. Frank Dobie, House’s fellow Texas writer, called him “a poet

as well as historian and wordwielder.”

EARLY NEWSPAPERS - Writing about early newspapers, particularly

those published for a relatively short period of time, is fraught

with problems. Even if copies of such newspapers are available,

the files are often incomplete, and relatively few files have been

digitized, especially with any degree of completeness. Many paper

files of older newspapers have deteriorated to the extent they may

not be usable, since most newspapers are printed on newsprint, a

very poor quality of paper. Beginning & ending dates of a particular

newspaper are often difficult if not impossible to determine. It

may be difficult to determine publishers, places of publication,

and any title changes.

That said, the consensus is that the first newspaper published in

Ranger was The Ranger Chief. It was published in 1885 and for

sometime thereafter by a Mr. Kirgan.

Dan H. Biggers published The Ranger Atlas beginning in the latter

part of 1891. Publication lasted only a short time and ceased when

Biggers moved to Strawn.

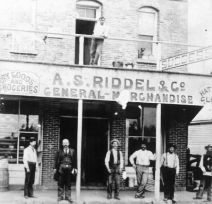

Jan Byrd began publishing The Ranger Success in 1895. It was pub-

lished on the second floor above A.S. Riddell & Co. (pictured here

is the building on Main Street that years later became the post

office). After a short time Byrd sold his interest to Dr. W. F.

Baylus, who changed the name to The Ranger Chronicle. Yet another

later owner continued weekly publication but changed the name to

The Leader. The subscription price was one dollar a year.

Mark Carothers bought the paper in 1912 and continued it as a

weekly under the title The Ranger Record. Carothers, a musician

as well as a newspaperman, organized one of the first bands in

Ranger. The Ranger Record continued until 1919, when it was sold

to the Times Publishing Company. After its purchase of The Ranger

Record, the Times Publishing Company stopped its publication and

began publishing The Ranger Daily Times. The first issue came

out June 1, 1919. Hamilton Wright, the first editor, recalled

in a 1939 interview that at the time of the first issue, there

were no subscribers. However, employees put the first issue

out on the streets, and in a short time 5,000 copies were sold.

The Ranger Daily Times is unusual in that a supposedly more or

less complete file, including its later title, The Ranger Times,

was microfilmed.

Established by John M. Gholson, Rip Galloway, and possibly others,

The Eastland County News was published as a weekly beginning in

late 1926 through July 1935, when the Times Publishing Company

took it over. The Loud Speaker, possibly reflecting a name change

of The Eastland County News, was published for a period of time

in the 1930’s. The Ranger Weekly Times began publication in

1934, covering not only Ranger but its entire trade area. How

long it lasted is unknown.

The Ranger Daily Times was the first daily published in Eastland

County, but it was not the first newspaper. Edwin T. Cox, early

Eastland County historian, said that the first newspaper published

in the county was The Eastland Review. It began publication some-

time in 1876 and was published until 1882 by E. W. Davenport. Like

many frontier newspapers, its equipment consisted of a hand press

and a few cases of type.

Freedom of the press was as much an issue in those days as it is

now. In a 1939 interview, F. D. Hicks, an early reporter for The

Ranger Daily Times, said that in the early days of the newspaper,

the chief of police warned that if a certain story were published,

the newspaper would be “blown to hell.” Newspaper employees were

asked whether or not they thought the story should be published,

and they unanimously said yes. The story was published, and the

editor was pistol whipped. However, the newspaper was not “blown

to hell” but survived. Photo courtesy of Ranger Historical

Preservation Society

A.S. Riddell & Co. building

A.S. Riddell & Co. building

W.K. GORDON - If it hadn’t been for W. K. Gordon’s persistence,

there might not have been a Ranger oil boom. As head of the Texas

and Pacific Coal Company’s coal mining operation at Thurber, he became

convinced of the existence of oil and gas deposits near Thurber. After

he discovered oil near Strawn, a little northwest of Thurber, in 1915,

possibly while searching for new veins of coal, the Company approved

his further oil and gas explorations despite the naysaying of trained

geologists.

By 1917 the worst drought that anyone could remember was devastating

the chiefly agrarian economy of the Ranger area. A group of Ranger

businessmen offered Gordon leases on 25,000 acres of land if he would

finance the drilling of some exploratory wells in the Ranger area.

The extent of the leases differs depending on the reporting source,

but the consensus is that it was a lot of land.

The first well, on the Nannie Walker farm north of Ranger, was a

disappointment, since it initially started spewing gas, but the

second well, on the John McCleskey farm a little south of downtown

Ranger, came in at a little over 3,400 feet. The Texas and Pacific

Coal Company had told Gordon to stop drilling at 3,200 feet if he

had not found oil, but he persuaded the Company to allow him to

continue drilling The resulting well tapped into the vast Ranger

oilfield and ushered in the Ranger oil boom.

William Knox Gordon was born January 26, 1862 in Loriella, Virginia,

the son of Cosmo and Adelaide (Lorimer) Gordon. As a young man he

became a surveyor’s helper, and within a few years he was a surveyor

and civil engineer. After working in South Carolina, Georgia,

Virginia, and Mississippi, he came to Texas in 1889 to survey a

proposed railroad between Dublin & Thurber (some sources say Dublin

and Strawn). The Texas and Pacific Coal Company offered him a job

as a civil and mining engineer in Thurber.

Although he had no previous mining experience, he eventually patented

several technical improvements for the mines. In 1899 Gordon became

a Company vice-president and manager of the Company-owned town of

Thurber and mining operations there. Residents of Thurber including

the miners came to respect Gordon as an honest and fair employer.

Gordon married Fay Kearby in 1903. They had three children, only

one of whom (W. K. Gordon, Jr.) survived childhood.

Gordon retired from the Company in the early 1920s and became a highly

successful independent oil and gas producer. He returned to the

Company as president of its board of directors from 1934 until his

death. Gordon died in Fort Worth March 13, 1949.

The W. K. Gordon Center for Industrial History of Texas was named in

honor of W. K. Gordon and perpetuates the legacy of his role in oil

discovery in north central Texas and in the industrial development

of Thurber. Located on Interstate 20 at Thurber, it opened in 2002

as a museum and research facility of Tarleton University. The

Center was made possible by the generosity of Mrs. W. K. Gordon,

Jr. (Anna Melissa Hogsett Gordon) & the W. K. Gordon, Jr. Foundation,

of which Mrs. Gordon was trustee. It contains exhibits of Thurber’s

history, the Ranger oilfield, and other centers of industrial

development in Texas.

The town of Gordon, in Palo Pinto County, was not named for W. K.

Gordon. It was named for H.L. Gordon, the civil engineer who

surveyed the site for Gordon in the 1880s.

W.K. Gordon

W.K. Gordon

SHOOTING AN OIL WELL - When an oil well had been drilled to the depth

at which oil was expected and little or none was forthcoming, or even

if a well was producing but only moderately so, the driller could call

in the services of a “shooter.” The shooter had one of the most

dangerous jobs around the oilfield. His job was to drop containers of

nitroglycerin, called “hell’s broth” or “soup,” into the well, followed

by a “go-devil” filled with lighted dynamite. He would then run for

safety. The explosion would rip into rock formations, freeing the

oil to come through if there was any, or increasing the flow in the

case of a producing well, possibly turning it into a gusher.

One oilfield observer reminisced about watching a shooter dropping the

“soup” and “go-devil” into a particular well: “A few seconds later,

there was a jar about like someone hitting a log you were standing on

with an ax. There came a shower of dirt and rocks, and then a column

of gleaming oil soared halfway up the derrick.”

The amount of nitroglycerin could vary, from typically a few hundred

quarts or less to many more. Boyce House, early reporter/editor of

The Ranger Daily Times, said that Jack Rapp, from Ranger, shot more

wells than any other shooter and had set off a 2,000-quart shot of

nitroglycerin, the biggest shot ever known.

Everything used in shooting a well was far from fail-safe. Even mixing

the nitroglycerin, a combination of sulfuric and nitric acids and

glycerin oil, was dangerous. Containers were loaded into rubber-lined

compartments designed to resist leakage and jarring en route to the

well. Dirt roads to oilfields were often bumpy and also often the

sites of disasters with nitroglycerin trucks. One oilfield observer

said that when an oilfield worker driving a vehicle saw a nitro truck

coming, he would pull off to the side of the road as far as possible

and breathe more easily when the truck was far down the road! Oilfield

workers rarely hitched rides on nitro trucks.

The average tenure of a shooter was about three years: if he hadn’t

been killed by then, he probably had had enough close calls that he

would be on the point of deciding to find a less dangerous, if not

as well-paying, way of making a living.

The first issue of The Ranger Daily Times, June 1, 1919, reported

on a fatal accident involving a nitro truck. The driver had been

crossing a bridge when his truck blew up. The bridge was demolished

as well, and the driver was killed.

TICKVILLE BAND - Ranger had a number of bands in the early days. One

of the first was organized by Mark Carothers, musician, newspaperman,

and owner of The Ranger Record. The period of time in which his band

performed is not known, but it was likely sometime in the teens, coin-

ciding with his Ranger newspaper publishing. The Ranger High School

band was organized in 1924, and it and the Ranger Junior College band

were combined in the early years.

Ranger’s best-known band was the Tickville Band, organized in the late

1920’s or early 1930’s under the auspices of the Carl Barnes Post No.

69 of the American Legion of Ranger. Directed by Dr. Harry A. Logsdon,

the highly popular band acquired a reputation over a wide area, not

just in Ranger. It became so popular that it had to start charging

for out-oftown performances. It usually played only for clubs and

welfare programs.

A 1934/35 report on Tickville Band activities provides an idea of the

scope of its performances: the Christmas Cheer Fund dance sponsored by

the Elks Club, Ranger; a benefit dance for the BPO Elks, Breckenridge;

annual banquet of the Chamber of Commerce, Munday; annual Ladies’ Banquet

sponsored by the Lion’s Club, Abilene; annual Spring Clinical Congress

of Physicians and Surgeons, Dallas; and a District Convention of the

American Legion, Ranger. Among other places in which the Band performed

were Desdemona, Mineral Wells, Eastland, Stephenville, Seymour, Rising

Star, and Brady.

A physician, a bank cashier, an assistant superintendent of a gasoline

plant, and a dentist were among the musicians. The 1934/35 report on

the Band’s activities listed the following members about that time: Dr.

Harry A. Logsdon, J. J. Kelly, W. I. Wright, Charles J. Moore, Harry

Henry, Clayton Hunt, Johnny Ducker, Lonnie Herring, Henry Hannold, and

John C. Turpin.

The Band had fun with its music making, as did audiences. Boyce House,

early reporter/editor of The Ranger Daily Times, wrote about the Tickville

Band in I Give You Texas, his syndicated column. In jest, he described

the group as “ an aggregation of music maulers,” made up, he said, of

some of Ranger’s leading citizens. He described a performance he had

attended: “The doctor was featured in a ukulele number, and the cashier

shone in what was announced as ‘The Double Eagle March.’ The gasoline

plant official went to town with thimbles on a washboard, but the climax

came when the dentist became entangled in the strings of his bull fiddle

and had to be extricated.”

Tickville Band 1932 Kinberg Photo

Courtesy of Dorothy Henry Beames

Tickville Band 1932 Kinberg Photo

Courtesy of Dorothy Henry Beames

Finding this little part of history about Ranger interesting, we wondered

if there was any more information out there about the Tickville Band. We

reached out to Ms. Pruett who is well known in the Ranger area for her vast

knowledge of historical information and she was able to contribute the

additional tidbits of information about the Tickville Band/Kinberg Photo:

Two of the band members, Dr. Harry A. Logston (1933-1937) and J.J. Kelly

(1943-1947) were past Mayors of Ranger. Harry Henry was the father of

Ranger resident Dorothy Henry Beames.

The Kinberg name, Kinberg Studio/John Kinberg (residence), was listed in

the 1928-1929 Ranger City Directory with an address of 401 Main Street.

The Kinberg’s were not listed in the 1936 Ranger City Directory however

John Kinberg, according to Eastland Cemetery Records, died in 1954 and

is buried in the Eastland Cemetery with his wife, Bess, who died in 1976

and 2 Kinberg children with no birth or death dates.

ST. RITA'S CATHOLIC CHURCH & PARISH SCHOOL - 2018 marks the hundredth

anniversary of the Catholic Church in Ranger. Rev. Rudolph A. Gerken

of Abilene visited Ranger in August

1918 to establish a parish (Ranger

was then in Abilene’s Catholic Church

mission territory). Mass was said

first in the home of Joseph F. Casey,

in the Premier Pipe Line Camp. Mass

was said later in the display room of

the Leiveille-Maher Motor Company and

in a tent until the church opened Oct.

20, 1919 for celebration of mass. The

church, on Blackwell Road, was completed

February 23, 1920 and was dedicated by

Bishop Lynch of Dallas on March 27, 1920.

of Abilene visited Ranger in August

1918 to establish a parish (Ranger

was then in Abilene’s Catholic Church

mission territory). Mass was said

first in the home of Joseph F. Casey,

in the Premier Pipe Line Camp. Mass

was said later in the display room of

the Leiveille-Maher Motor Company and

in a tent until the church opened Oct.

20, 1919 for celebration of mass. The

church, on Blackwell Road, was completed

February 23, 1920 and was dedicated by

Bishop Lynch of Dallas on March 27, 1920.

Mission churches of Ranger’s St. Rita’s Catholic Church were St. John’s in

Strawn, St. Francis Catholic Church in Eastland, and Holy Rosary Catholic

Church in Cisco.

Two buildings were purchased from the Phillips Petroleum Company for $7,500

and moved to the church grounds to serve as a school. Rev. Gerken, the

church’s first priest, requested that seven Sisters from the Sisters of

Charity of Incarnate Word, San Antonio, be sent to run the school. It

officially opened in September 1921, with elementary and high school

grades. Initially it was predicted that enrollment would be about 70

students, but the school rapidly grew to about 125 students. The high

school program, however, declined in enrollment and was dropped in 1931.

In 1924 a separate school for MexicanAmerican children was opened just

north of the church, but it closed several years later.

St. Rita’s Parish School became known for its high standards, quality

of instruction, and strict discipline. It was open to nonCatholics as

well as Catholics. Beginning in 1923 and for a number of years a

Parish school bus picked up children in Eastland and Cisco and carried

them to and from Ranger. St. Rita’s Parish School, after educating

students for a little over 30 years, closed permanently at the end of

the 1952 school year. Thereafter some elementary school students went

to Hodges Oak Park School, and others went to Young School.

After the school closed, the main school building was moved to the Ranger

Junior College campus, where it served for several years as the girls’

dormitory, named in honor of Mary Frances Jameson. It later burned

down. The other building (pictured here) is now the Parish Hall. When

St. Rita’s Parish School was still operating, the building was used

for school boarders, a cafeteria, classrooms, and a school auditorium.

TEXAS & PACIFIC RAILWAY COMPANY - Once the Indians presented no further

threat, the major factor in the development of the West was the coming

of the railroad. It was a sure sign that the area would indeed be

developed. In many ways the railroad brought a close to pioneer life,

opening up the area to commercial farming and trade. The Texas and

Pacific Railway Company issued thousands of copies of a 42-page booklet

extolling the advantages of the West and offered ultra-low fares to

prospective settlers. T&P’s railroad reached Eastland County in 1880.

Between then and 1900, the population of the county more than tripled,

from 4,855 in 1880 to 17,971 by 1900, no doubt in large part due to

the encouragement the Company offered to immigration.

T&P was the only railroad in Texas and one of the few in the United

States to operate under a federal charter. T&P was given the right

to build a railroad from Marshall, Texas to San Diego, California as

part of a project, conceived before the Civil War, to build a southern

transcontinental railroad. Construction began in 1871, and after some

setbacks the railroad had reached Fort Worth by 1876. By 1880 the

railroad was adding about 30 miles of track a month. At one time about

8,000 men were on the payroll. Railroad pay ranged from $1.15 to

$1.50 a day.

The project’s goal was to follow the 32nd parallel as closely as

practical. The path of a railroad could determine the location of a

town, and so it was with Ranger. Following the natural contour of the

land insofar as possible, T&P built its railroad west of Ranger Camp

Valley, but the inhabitants had already moved to be near the planned

railroad. It reached the settlement October 15, 1880. T&P bought 160

acres from Isham G. Searcey for a town site, which it called Ranger

in recognition of the Texas Rangers and Ranger Camp Valley. In 1882

the only train robbery ever in the county took place in Ranger.

The Ranger oil boom had an enormous impact on T&P’s receipts there. In

one pre-boom year they totaled $94,098. In 1918, after the beginning

of the boom, receipts were $2,349,334. In 1919 they rose to $8,146,309.

By 1923, however, after the boom was over, receipts fell back to $1,646,744.

One agent, a helper, and three telegraphers made up the pre-boom staff.

During the boom the staff grew to one agent, an assistant agent, and 26

clerks. Between 30 and 40 laborers worked on the freight platform loading

and unloading freight.

In a history of T&P compiled by the Company in 1946, it acknowledged

that discovery of oil in Ranger gave T&P its first experience in coping

with the transporting of oil. It said, “The knowhow in handling the

transportation problems of the oil industry was of inestimable value

later.”

John Rust, a teenager in Ranger during the oil boom, reminisced about

trains during the oil boom many years later for the Oral History of the

Texas Oil Industry (Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University

of Texas at Austin). He said that there were five daily trains from

the east and five from the west. Each of the seven to fifteen cars on

each train was full, with many travelers standing in the aisles. Many

had to stand for the entire distance from Fort Worth or Abilene or even

farther. Some rode on top of the coaches and boxcars, and some even

rode on the cowcatcher. Riding the trains was not a pleasant experience:

they were often late by as much as twelve hours.

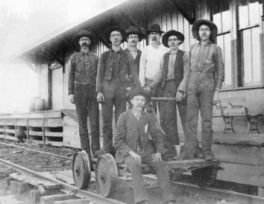

T&P’s first depot, a small frame building (pictured here), was on the

east side of the tracks and on the north side of the railroad crossing

where Main Street adjoins Highway 80. It burned down in 1907. It was

replaced by a larger depot, also on the north side of the crossing.

That depot was remodeled and converted into the freight depot when the

new depot, made of brick, opened on the south side of the crossing in

1923. A 1929 newspaper article reported that in that year T&P had

eight passenger trains a day through Ranger.

In 1918 the Missouri Pacific Railroad Company began buying stock in T&P.

By 1930 Mo-Pac owned enough T&P stock to give it nearly 75 per cent

ownership. By the end of 1974 it owned nearly 97 per cent of the stock.

In 1976 T&P was merged into Mo-Pac. Mo-Pac applied to the Texas Railroad

Commission to abandon its line that had run through Ranger. Mo-Pac planned

to dismantle the 1923 depot, but the City of Ranger took it over. The

Chamber of Commerce was re-located there, and in 1982, the Roaring Ranger

Museum opened in the former depot.

Some railroad workers By Ranger’s

first train depot. Photo courtesy

of Ranger Historical Preservation

Society.

Some railroad workers By Ranger’s

first train depot. Photo courtesy

of Ranger Historical Preservation

Society.

RANGER'S FIRST HOSPITAL - Ranger did not have a hospital before the oil

boom. Patients needing hospitalization for surgery or for other reasons

were sent to Fort Worth or Abilene. A privately owned hospital was

opened in Ranger in 1919 by Lena Clarmont on Haig Street, a two-block

street just west of Blundell Street and about two blocks south of Strawn

Road. Clarmont bought a house north of the hospital to house hospital

employees.

The hospital, which she called “Ranger General Hospital,” was beset with

problems from the very beginning. There was no running water: all water

used in patients’ rooms and elsewhere in the hospital had to be carried

by hand. Sewage disposal was inadequate, & electricity was undependable.

The lack of dependable lighting caused problems especially with operations.

Clarmont tried to cope with the electrical problems by installing a

generator. She and her staff and a hospital expert from New York worked

tirelessly to resolve problems, but the odds seemed against them, especially

the lack of running water. There was another problem. The City would

send patients to the hospital who could not pay, but according to a 1919

newspaper article, the City did not reimburse Ranger General Hospital for

their care. All her problems notwithstanding, Clarmont planned to expand

the hospital beyond its capacity of 41 patients.

It was clear to Ranger doctors that something had to be done. A group of

doctors who were referred to as the Ranger Medical Society met in early

1920 to discuss a proposed Physicians’ and Surgeons’ Hospital, which

would be a two-story building with 50 private rooms and wards with a

capacity of 100 beds. It would at the west end of Main Street, in an

area called Ranger Heights, overlooking Mirror Lake. Nothing came of

this proposal, but in 1921 a bond issue was considered as a way of

paying the City’s share of a City-County Hospital.

Finally in March 1924 the hospital, called “Ranger City-County Hospital”

(also called “Ranger General Hospital”), built at a cost of $75,000,

opened on a hill just off West Pine Street & at the west end of Mesquite

Street, where it remained until it closed and a new hospital building

opened on Highway 80 West. The hospital accepted charity patients as

well as paying patients. It received funding from both the City of

Ranger and Eastland County, and management was under a hospital board

appointed by the Ranger City Commission and the County Commissioners

Court.

Ranger's First Hospital, 1924,

Ranger General Hospital. Photo

Courtesy Ranger Historical

Preservation Society.

Ranger's First Hospital, 1924,

Ranger General Hospital. Photo

Courtesy Ranger Historical

Preservation Society.

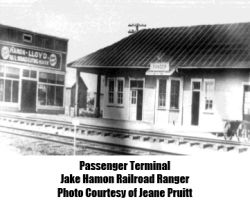

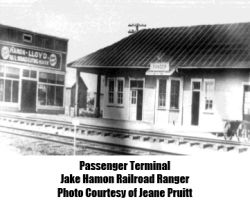

THE JAKE HAMON RAILROAD - The Texas & Pacific Railway Company’s railroad

reached Ranger October 15, 1880, providing service east and west. Jacob

(“Jake”) L. Hamon, newly arrived in Ranger from Ardmore, Oklahoma during

the Ranger oil boom, saw a need—and business opportunity—for a train line

running north and south. In 1918 drilling for oil brought in major

producers in both Breckenridge and Desdemona (also known as “Hogtown” or

"Hog Town”). Both places showed promise of becoming boom towns, as Ranger

had become in 1917. There were no railroads in either Breckenridge or

Desdemona, and the cost of hauling oil and drilling equipment by wagon or

truck was almost prohibitive.

Hamon and his fellow railroad promoters, among them Frank Kell, Edwin E.

Hobby, Joseph A. Kemp, A. R. McLennan (the latter from Ranger), and others

incorporated September 26, 1919 with the objective of building a railroad

67 miles long from Dublin to Breckenridge.

The official name was the Wichita Falls, Ranger, and Fort Worth Railroad

Company. Wichita Falls was in the name because promoters envisioned the

line eventually being extended by nine miles north from Breckenridge,

tying in at Jimkurn, in northern Stephens County, with the Wichita Falls

and Southern Railroad, which went to Wichita Falls. Ranger was in the

official title because of its central location on the planned line,

because it was the location of the 1917 oil boom, and, too, it was where

the offices of Jake Hamon Company president, would be located. Fort

Worth was in the title because promoters planned a tie-in at Dublin with

the Frisco System (St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company), which went

to Fort Worth, among other places in Texas and eight other states.

The Wichita Falls, Ranger, and Fort Worth Railroad Company was known by

a number of names: “Hamon-Kell” (Frank Kell along with Jake Hamon was

a major investor), “Hamon and Kell,” and “Kell-Hamon.” By far the name

by which the railroad became best known, however, was the “Jake Hamon

Railroad.”

Hamon’s first job had been clerking in a country store, but when he

received a law degree from the University of Kansas, he became Lawton,

Oklahoma’s first city attorney. He soon became interested in railroad

building. His first big ventures were building railroads from Lawton

to Ardmore and from Wichita Falls, Texas to Oklahoma City. Backed by

John Ringling, of circus fame, he built a railroad from Ardmore to

Ringling, Oklahoma. He began speculating in oil production, amassing

a fortune chiefly by buying oil at low prices and later selling high.

Thus Hamon arrived in Ranger with experience in railroad building and

oil.

Hamon and Frank Kell and possibly other investors put up the estimated

$5,000,000 that the railroad was expected to cost. However, towns were

expected to “subscribe” to the enterprise, presumably to pay for right

of way. A group of Ranger businessmen felt that the railroad was of

vital importance to Ranger and “subscribed” $250,000. Breckenridge,

too, raised money. Desdemona, however, either would not or could not,

and in retaliation the Company routed its railroad to bypass Desdemona.

Hamon laid out a town site about two miles from Desdemona, just over

the Comanche County line, and named it “Jakehamon” (one word). The

Company expected that Desdemona, at that time a town of about 16,000,

would simply close up and move in its entirety to Jakehamon. The new

town site was initially the scene of frenzied investing, with investors

lined up to purchase lots. Desdemona may not have been the only place

that the Jake Hamon Railroad bypassed out of retaliation for not “sub-

scribing.” Sources differ on this issue.

Other town sites were laid out along the route of the Jake Hamon Railroad.

Edhobby (named for promoter Edwin Hobby), eight miles north of Jakehamon

and twelve miles southeast of Ranger, was intended to be the center of

production for the northern extension of the Hog Creek Oil Field (i.e.,

Desdemona). Breckwalker (named for oilman Breckenridge Stephens Walker),

nine miles south of Breckenridge, was laid out by Hamon to be a supply

center for oil fields in the area. A Dec. 1919 news article announced

that the Company would open the new Stephens County town site of Frankell

(named for Frank Kell) to investors that month. It would be the first

“new” town that the Jake Hamon Railroad would go through, the article

said.

Track laying began in Ranger in February 1920 and proceeded at the rate

of about a mile a day. The railroad was planned mainly to serve oil

interests, but initially it also offered passenger service. A passenger

depot (pictured here) was built in Ranger on Hunt Street, which the rail-

road crossed. Passengers could eat at the Hamon-Lloyd Railroad Eating

House, adjacent to the depot. The track needed to cross the Texas &

Pacific railroad a short distance north from downtown Ranger. Repeated

requests to T&P for permission were not answered, and finally Hamon got

a court order authorizing the crossing. One night shortly thereafter,

he and a large crew along with armed guards showed up, cut the T&P tracks,

and created the crossing. T&P officials were furious, since their trains

were tied up from both directions until the Hamon Railroad crossing was

completed.

In 1921 the Company was able to carry out its plan of extending the rail-

road nine miles to Jimkurn. By the end of that year, however, the Company

was in receivership, which lasted until 1926. Beginning in 1927 the

railroad was leased by the Wichita Falls and Southern Railroad. In the

meantime Jake Hamon had been killed in 1920 by a gunshot wound inflicted,

some newspapers claimed, by his alleged mistress. Still other newspaper

accounts said that the gunshot wound had been accidentally self-inflicted.

In his memory all trains on the Jake Hamon Railroad stopped for ten minutes

at the time of his funeral, and operations on all his oil leases ceased

for one hour.

The town sites of Jakehamon, Edhobby, and Breckwalker never became towns

of any substantial size, let alone the big oil boom towns that Hamon and

fellow promoters had envisioned, and all three were listed as part of

Hamon’s estate at the time of his death. Frankell, too, never became a

big town but at one time had two schools and a post office. On some

maps it continues as “Frankell Community.” In 1954 the Wichita Falls

and Southern Railroad was abandoned, along with virtually all the Jake

Hamon Railroad it had leased. Eventually most of the Jake Hamon Railroad

tracks and ties were taken up.

JOHN GHOLSON - was a civic leader, businessman, & oilman. He was Ranger’s

second mayor, serving from April 1921 to May 1923. Many of his contem-

poraries considered Gholson and M. H. Hagaman the two men who did more

for Ranger than anyone else.

In 1917 he headed a delegation of Ranger businessmen who approached W.K.

Gordon, President of the Texas & Pacific Coal Company at Thurber, with

a proposal for drilling some experimental oil wells in the Ranger area.

Gholson was a leader in getting together leases on thousands of acres

that induced T&P Coal to drill, thereby bringing in the Ranger oil boom

when the experimental drilling ultimately turned out to be highly

successful. Toward the end of the boom, when it was clear to many that

over-drilling was rapidly depleting oil reserves, Gholson was one of the

first oilmen to lead a voluntary proration effort, which emphasized the

waste caused by over-production.

Gholson was one of the organizers of the Chamber of Commerce, which began

in 1918. A 1919 newspaper article gave the Chamber of Commerce credit

for the “efficient progress which the City of Ranger has made since it

came into the world’s limelight as an oil field center and as one of the

fastest growing towns on the continent.” Among Gholson’s many other

civic contributions was service on the first City Commission and on the

school board and as president of the Board of Education for Ranger Jr.

College in 1926/27, its initial year of operation. After the oil boom

was over and the City’s treasury was running low, Gholson at one time

personally advanced $25,000 for teachers’ salaries.

Realizing the importance of railroads, Gholson was one of the supporters

of the Wichita Falls, Ranger & Fort Worth Railroad Company (the Jake

Hamon Railroad). He persuaded a company to build the Gholson Hotel,

which opened in 1921, in exchange for a lease on land he owned.

John Mercer Gholson was born near Monticello, Wayne County, Kentucky

August 29, 1876, the son of Ben Franklin Gholson & Martha Black Gholson.

He came to Texas with his family in 1885. They settled first in Fort

Worth and then in Millsap. He came to Ranger when he was 16 and worked

in a mercantile store. He eventually became a partner in the Terrell

& Gholson Mercantile Company. That partnership continued until 1918,

when Gholson formed a company, Gholson, Moorman, and Dorsey, which

brought in some major oil producers.

Gholson married Mary Serena Rawls (called “Mollie”), and they had four

children: Helen, John D, Howard, and Charles. After a long-standing

interest in Ranger’s well being and having played major roles in many

civic improvements, Gholson died July 20, 1932. In his honor all

businesses closed the afternoon of his funeral.

John Gholson (1876-1932)

John Gholson (1876-1932)

ARTICLES TO CONTINUE MONTHLY

HISTORY OF RANGER - Page 1 Page 2 Page 4

FAMOUS VISITORS - Ranger had a steady stream of visitors during the oil boom and for years thereafter. Among them were the famous, the not-famous—and the infamous. In the latter group were Bonnie & Clyde, of the Clyde Barrow gang, who “visited” the Ranger National Guard Armory in February 1934, helping themselves to an arsenal of weapons. However, that’s another story… One of the early famous visitors was United States Ex-President William Howard Taft. Elected President in 1908, he failed to be re-elected in 1912, yielding the Presidency to Woodrow Wilson. Taft became a professor of law at Yale University after leaving the White House and, after several other Government positions, was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1921. Before he began serving on the Supreme Court, he visited Ranger. Before the Former Presidents Act of 1958, the United States Secret Service did not provide protection for former Presidents, so Taft mingled with the crowds on the streets of Ranger unprotected and unnoticed. So far as is known, his only official appearance in Ranger was before the newly organized 1920 Club, a women’s study club. One Club member wrote on her 1920/1921 year book that Club members had to hunt for the piano music to “Hail to the Chief” so that their guest speaker could be properly welcomed! Rex Beach, prolific American novelist and playwright (as well as Olympic water polo player), visited Ranger during the oil boom to do research for his novel, Flowing Gold. Published in 1922, it was made into a movie directed by Alfred E. Green and produced by Warner Brothers in 1940. It is set in American oilfields in general and not specifically the Ranger oilfield. After years of unsuccessful prospecting for gold, Beach had turned to writing. Most of his novels, like Flowing Gold, are adventure stories, and many were made into movies. Billy Sunday, the best known and most influential American evangelist in the first two decades of the twentieth century, visited Ranger during the oil boom, preaching to large crowds in the streets. At the time of his Ranger visit, he was attracting the largest crowds of any evangelist. He was especially well known for his strong support of Prohibition. His preaching possibly was a strong factor in the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919, which outlawed alcoholic beverages in the United States. Aviatrix Amelia Earhart landed her Pitcairn Autogiro plane (pictured above) in Ranger June 16, 1931 to refuel. The newspaper headline read: “Miss Earhart Lands Windmill in Ranger.” Her stop had not been announced, but a large crowd gathered while the Lone Star Gas Company supplied 30 gallons of gasoline. She told observers that her plane’s highest speed was 110 miles an hour, with a cruising speed of 80 miles an hour. She said that at $15,000 it was expensive because it was handmade. Six years after her Ranger refueling stop, on July 2, 1937, while she and her navigator Fred Noonan were making a round-the-world attempt, her plane, a Lockheed Electra, disappeared in the Pacific, creating an as yet unsolved mystery.

POST OFFICE - The railroad reached Ranger on October 15, 1880, and the train depot served briefly as the post office before a post office was formally established December 27, 1880. James M. Davis, the first postmaster, kept the post office in his store, J. M. Davis and Bros., located in a small frame building on Main Street near the northwest corner of Main and Commerce Streets. At some point before the oil boom the post office moved to the south side of Main Street into a building that had earlier been occupied by the Albert S. Riddle store and, on the second floor, by an early Ranger newspaper, The Ranger Success. This building was in a row of buildings occupied years later by C. E. May Insurance, Greer’s Western Wear, and the Corner Drug Store. Pictured above is the post office in this location. Before the oil boom the post office was adequate for Ranger and adjacent rural areas. That changed quickly with the oil boom. For example, during the second quarter of 1897, the post office issued 157 money orders. In the last quarter of 1918, it issued 4,443 money orders. There were often long lines, stretching for blocks, of people waiting to get to the general delivery window. A Ranger Daily Times article reported that enterprising young men would often arrive at the post office early in the morning and then volunteer to sell their place in line to the highest bidder. The chamber of commerce began documenting the inadequacy of the mail system during the oil boom. It presented statistics of receipts to the postal authorities, and ultimately a new building was authorized. The new frame building opened on North Marston Street in 1919. That year the Post Office Department agreed to waive its requirement of paved streets for city delivery. That and the chamber of commerce’s agreement to name all streets and assign numbers to all houses greatly aided in mail delivery. Little more than a year later, in 1920, the post office moved again, this time to an even larger building at Elm and Rusk Streets. The Ranger post office had been promised four carriers, but the chamber of commerce discovered that no one wanted to work for a carrier’s salary of $100 a month, when many oilfield jobs paid more. The chamber of commerce authorized a supplement of $25 for each carrier’s salary in an effort to attract employees. Plans for a new post office to replace the one at Elm and Rusk Streets were announced in 1934, with $80,000 in government funds set aside for construction. The cornerstone of the new post office was unveiled in October 1937 as part of the celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the discovery of oil. The building, Ranger’s current post office, opened in January 1938 at the corner of North Austin and Walnut Streets. During the 1930’s and early 1940’s many murals were commissioned in public buildings across the economically depressed United States as an effort to employ artists. The Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project and other similar initiatives such as the Section of Fine Arts of the U. S. Treasury Department spearheaded these efforts. Emil Bisttram, a Hungarian-born artist, painted a mural, The Crossroads Town, in the Ranger post office in the latter program. The mural purports to depict Ranger as it was before the oil boom.

BOYCE HOUSE - was an early reporter/editor of The Ranger Daily Times and worked for other newspapers, including ones in Eastland, Cisco, Olney, Brady, and Fort Worth. He wrote a syndicated column, articles, poems, and books on oil boomtowns, including Ranger. In his work as a newspaperman he became known for his hard work and integrity. House was born on November 29,1896 in Piggott, Arkansas, the son of Noah E. and Margaret (O’Brien) House. Apparently because of his family’s financial circumstances, he was unable to go to college. Instead he went into journalism, one of his father’s occupations.

A.S. Riddell & Co. building

W.K. Gordon

Tickville Band 1932 Kinberg Photo Courtesy of Dorothy Henry Beames

of Abilene visited Ranger in August 1918 to establish a parish (Ranger was then in Abilene’s Catholic Church mission territory). Mass was said first in the home of Joseph F. Casey, in the Premier Pipe Line Camp. Mass was said later in the display room of the Leiveille-Maher Motor Company and in a tent until the church opened Oct. 20, 1919 for celebration of mass. The church, on Blackwell Road, was completed February 23, 1920 and was dedicated by Bishop Lynch of Dallas on March 27, 1920.

Some railroad workers By Ranger’s first train depot. Photo courtesy of Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

Ranger's First Hospital, 1924, Ranger General Hospital. Photo Courtesy Ranger Historical Preservation Society.

John Gholson (1876-1932)